It’s common knowledge that the GDPR makes it possible for sky-high fines to be imposed for contraventions, up to 20 million euros or, for a company, up to 4% of global turnover. This possibility has been created in order to stand up to international Big Tech, which is not worried about a fine of a just a few thousand euros. In the Netherlands, however, the highest fines have so far been imposed on government organisations. On 7 April 2022, the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration had the questionable honour of breaking its own record for fines – which stood at 2.7 million euros (for processing the dual nationality of recipients of a childcare allowance) – by 1 million euros. The Dutch Data Protection Authority (DPA) imposed a fine of 3.7 million euros in connection (briefly) with the Fraud Detection Scheme (FSV). This blog explains how the fine compares to previous fines imposed in the Netherlands, the DPA’s policy rules on fines, and what else all this means for data subjects.

Government organisations often the target

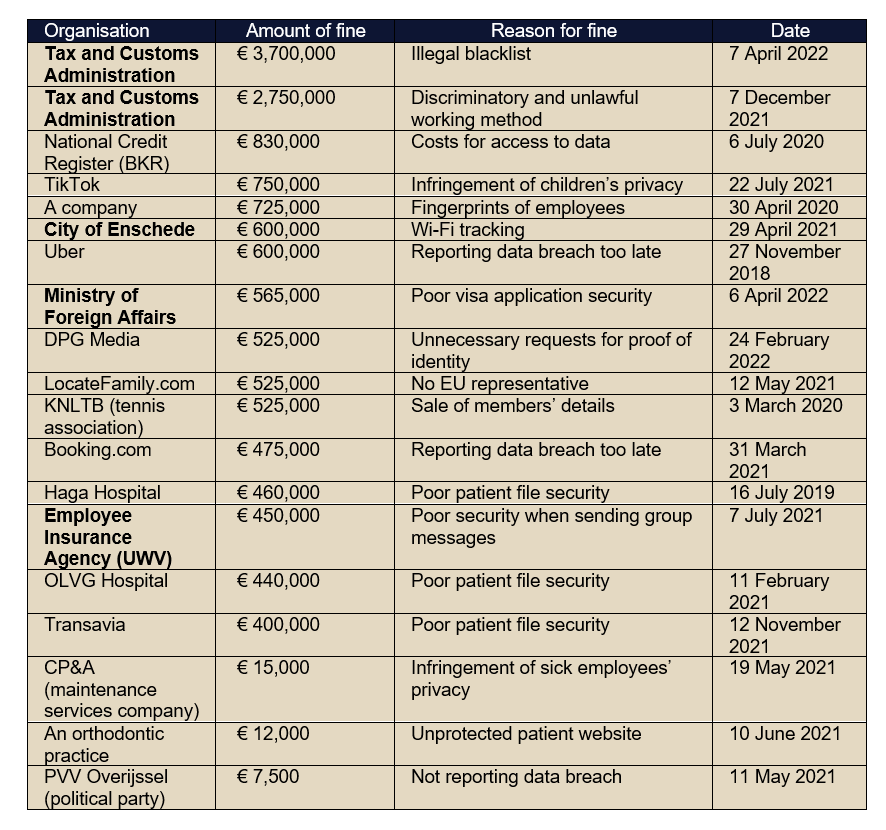

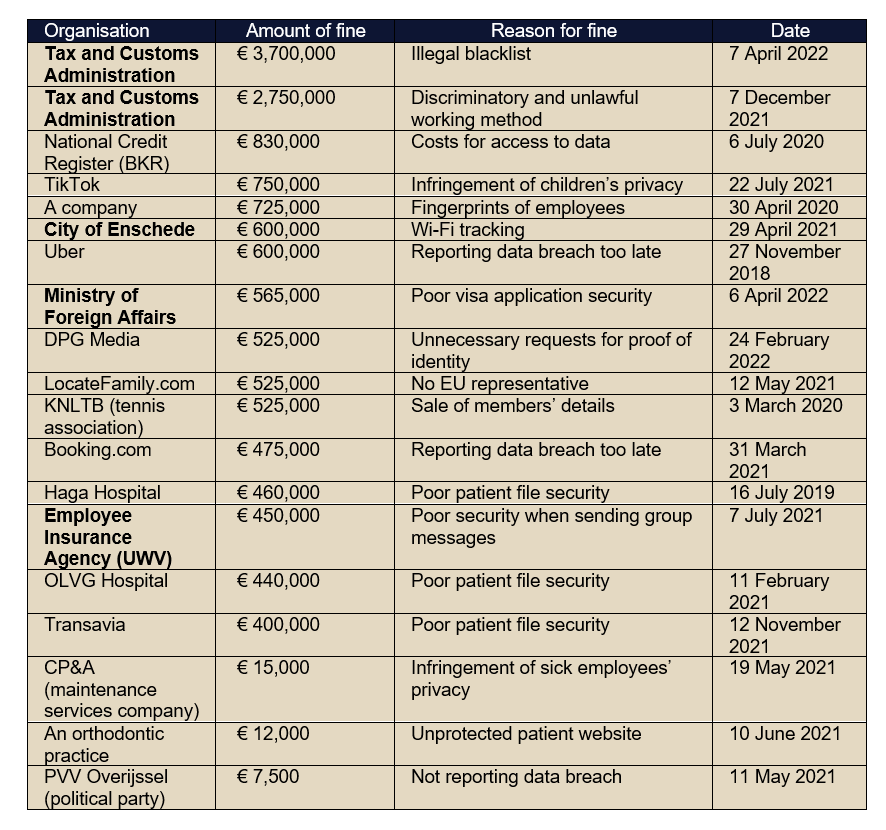

It is striking that the highest fines so far imposed by the DPA have been on government organisations, as the following overview shows.

Fines:

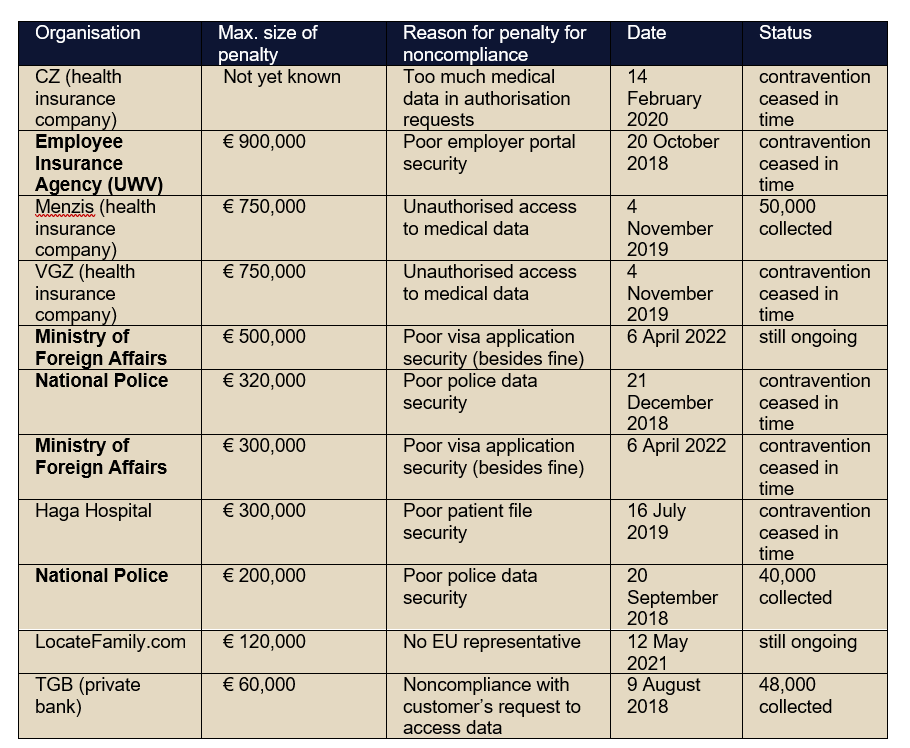

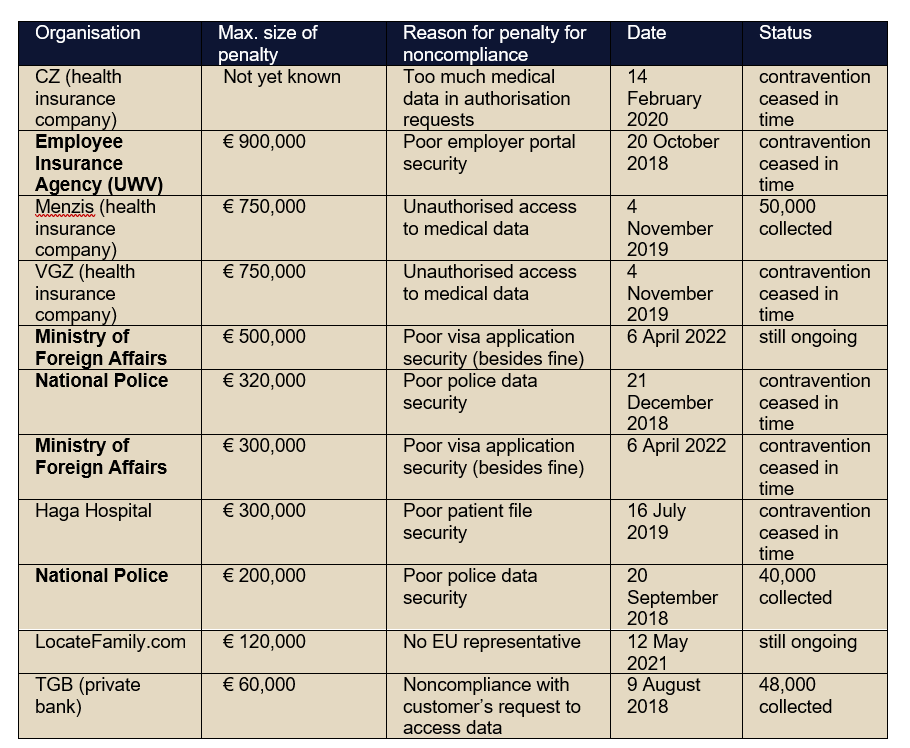

Order subject to penalty for noncompliance:

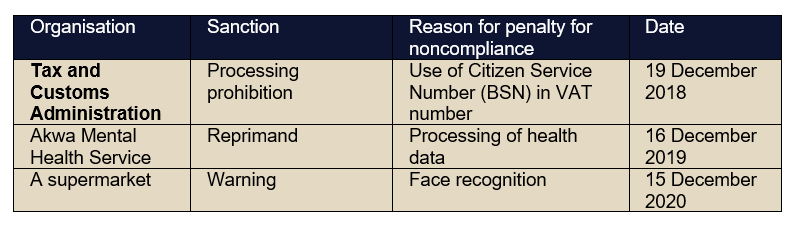

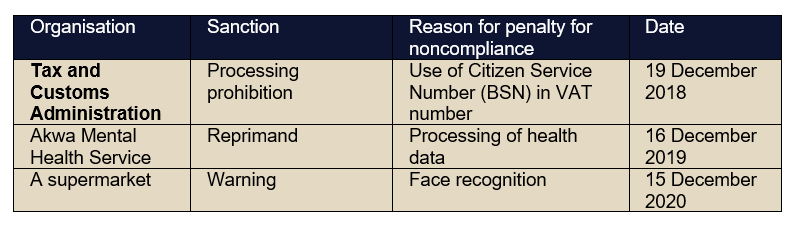

Other DPA sanctions:

That government organisations often contravene privacy legislation can be explained on the one hand by the fact that, by their nature, they process large quantities of often sensitive personal data. It is not surprising that things then sometimes go wrong. One hundred per cent compliance is a major challenge, if not an illusion. However, the contraventions listed above are not mistakes or formalities, but mostly serious violations of core principles of privacy law. The DPA apparently has its hands full as regards such violations.

The Fraud Detection Scheme (FSV)

The Fraud Detection Scheme (FSV) was an application that recorded signs of confirmed fraud and signs that could indicate an increased risk of tax and allowances fraud. In the FSV, the Tax and Customs Administration mainly included persons who had committed fraud and persons who were suspected of possibly committing tax or allowances fraud. The reason why people were placed on the list was often unclear. The FSV was used within the Tax and Customs Administration when assessing tax returns and applications for allowances, and was used to register information requests from other public authorities. The FSV was also consulted for risk modelling and when determining whether a fine should be imposed when collecting tax or allowances debts. For a person who was placed on the list for any reason whatsoever, this potentially had major consequences.

The DPA acknowledged that the tax legislation permits personal data to be collected for monitoring purposes in specific cases. However, the legislation does not provide sufficiently precise guidance as a basis for the separate, structural, extensive, and segment-overarching collection of multiple types of detailed (or too detailed) (special and criminal) personal data in the FSV. Moreover, processing in the FSV was unnecessary in order to fulfil the public oversight task of the Tax and Customs Administration. The principle of proportionality was not met because the contravention of the interests of those affected was disproportionate in relation to the purpose of the processing. The objectives of the FSV were also not properly defined and therefore unclear. The DPA also found that the principle of subsidiarity had not been met because the objective pursued could be achieved in different less far-reaching way, namely without using the FSV or by designing a different and more restricted application.

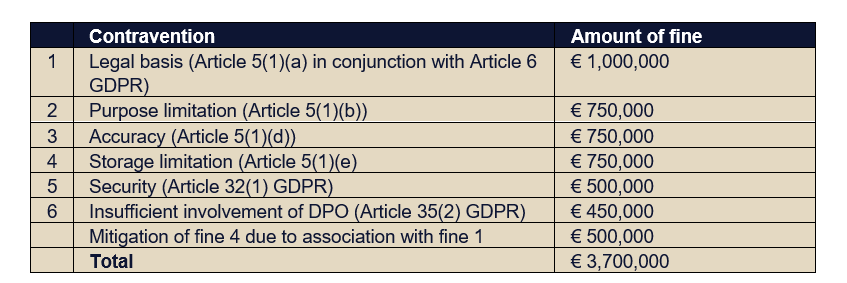

The DPA imposed a fine because of the lack of a basis, violation of the principles of purpose limitation, accuracy, and storage limitation, as well as for not having adequate security measures in place and for not involving the Data Protection Officer (DPO) properly and in a timely manner.

The latest Tax and Customs Authority fine is the sum total of various separate fines

In the DPA’s Fines Policy Rules, a range between EUR 450,000 and EUR 1,000,000 applies for the most serious contraventions. The basic fine of EUR 725,000 for such contraventions can be increased or reduced according to numerous factors such as the nature, severity and duration, the degree of negligence, and previous relevant contraventions (Section 7 of the Fines Policy Rules).

If the category of fine determined for the contravention does not allow for appropriate penalisation in the specific case, the DPA may, when determining the size of the fine, apply the bandwidth of the next higher category or of the next lower category. In the case of a repeat offence, the fine can also be increased by 50%.

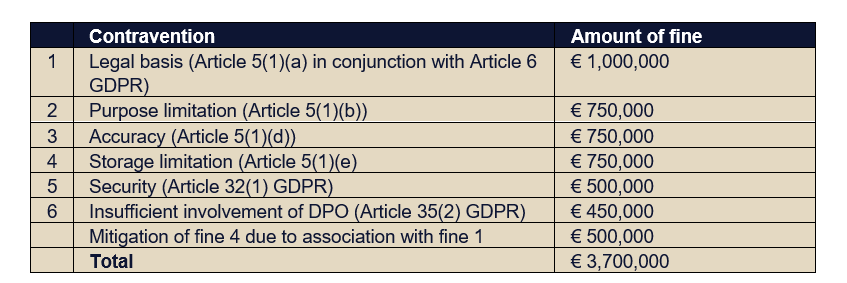

The fine of 3.7 million euros goes well beyond the highest category. This is because it is the sum total of separate fines for the various contraventions referred to.

The DPA imposed the following fines/partial fines:

The DPA found that the various contraventions are subject to separate fines because they infringe different interests. However, the DPA did mitigate the fine in respect of the storage restriction because of its association with the lack of a legal basis.

Section 10 of the Fines Policy Rules provides that in the case of multiple contraventions concerning the same or related processing activities, the total fine must not exceed the legal maximum penalty for the most serious contravention. That maximum would in this case be EUR 20 million, so there was indeed room for a higher penalty.

Robbing Peter to pay Paul

Especially in the case of the Tax and Customs Administration, which formally acts under the Minister of Finance, the fine is of course very much a matter of “robbing Peter to pay Paul”. The question then quickly arises as to whether it actually benefits the data subject. The fines do, however, send a clear signal, one that will not go unnoticed in political circles and that will also have its effect on the future from the legal point of view. When the fine was announced, the chairman of the DPA, Aleid Wolfsen, called for generous compensation for those affected who had been included in the FSV without any well-founded suspicion of fraud. The Dutch government has indicated that it is open to this. That is understandable: After all, in the absence of proper compensation, the issue would seem to be eminently suitable for a class action claim.

It’s common knowledge that the GDPR makes it possible for sky-high fines to be imposed for contraventions, up to 20 million euros or, for a company, up to 4% of global turnover. This possibility has been created in order to stand up to international Big Tech, which is not worried about a fine of a just a few thousand euros. In the Netherlands, however, the highest fines have so far been imposed on government organisations. On 7 April 2022, the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration had the questionable honour of breaking its own record for fines – which stood at 2.7 million euros (for processing the dual nationality of recipients of a childcare allowance) – by 1 million euros. The Dutch Data Protection Authority (DPA) imposed a fine of 3.7 million euros in connection (briefly) with the Fraud Detection Scheme (FSV). This blog explains how the fine compares to previous fines imposed in the Netherlands, the DPA’s policy rules on fines, and what else all this means for data subjects.

Government organisations often the target

It is striking that the highest fines so far imposed by the DPA have been on government organisations, as the following overview shows.

Fines:

Order subject to penalty for noncompliance:

Other DPA sanctions:

That government organisations often contravene privacy legislation can be explained on the one hand by the fact that, by their nature, they process large quantities of often sensitive personal data. It is not surprising that things then sometimes go wrong. One hundred per cent compliance is a major challenge, if not an illusion. However, the contraventions listed above are not mistakes or formalities, but mostly serious violations of core principles of privacy law. The DPA apparently has its hands full as regards such violations.

The Fraud Detection Scheme (FSV)

The Fraud Detection Scheme (FSV) was an application that recorded signs of confirmed fraud and signs that could indicate an increased risk of tax and allowances fraud. In the FSV, the Tax and Customs Administration mainly included persons who had committed fraud and persons who were suspected of possibly committing tax or allowances fraud. The reason why people were placed on the list was often unclear. The FSV was used within the Tax and Customs Administration when assessing tax returns and applications for allowances, and was used to register information requests from other public authorities. The FSV was also consulted for risk modelling and when determining whether a fine should be imposed when collecting tax or allowances debts. For a person who was placed on the list for any reason whatsoever, this potentially had major consequences.

The DPA acknowledged that the tax legislation permits personal data to be collected for monitoring purposes in specific cases. However, the legislation does not provide sufficiently precise guidance as a basis for the separate, structural, extensive, and segment-overarching collection of multiple types of detailed (or too detailed) (special and criminal) personal data in the FSV. Moreover, processing in the FSV was unnecessary in order to fulfil the public oversight task of the Tax and Customs Administration. The principle of proportionality was not met because the contravention of the interests of those affected was disproportionate in relation to the purpose of the processing. The objectives of the FSV were also not properly defined and therefore unclear. The DPA also found that the principle of subsidiarity had not been met because the objective pursued could be achieved in different less far-reaching way, namely without using the FSV or by designing a different and more restricted application.

The DPA imposed a fine because of the lack of a basis, violation of the principles of purpose limitation, accuracy, and storage limitation, as well as for not having adequate security measures in place and for not involving the Data Protection Officer (DPO) properly and in a timely manner.

The latest Tax and Customs Authority fine is the sum total of various separate fines

In the DPA’s Fines Policy Rules, a range between EUR 450,000 and EUR 1,000,000 applies for the most serious contraventions. The basic fine of EUR 725,000 for such contraventions can be increased or reduced according to numerous factors such as the nature, severity and duration, the degree of negligence, and previous relevant contraventions (Section 7 of the Fines Policy Rules).

If the category of fine determined for the contravention does not allow for appropriate penalisation in the specific case, the DPA may, when determining the size of the fine, apply the bandwidth of the next higher category or of the next lower category. In the case of a repeat offence, the fine can also be increased by 50%.

The fine of 3.7 million euros goes well beyond the highest category. This is because it is the sum total of separate fines for the various contraventions referred to.

The DPA imposed the following fines/partial fines:

The DPA found that the various contraventions are subject to separate fines because they infringe different interests. However, the DPA did mitigate the fine in respect of the storage restriction because of its association with the lack of a legal basis.

Section 10 of the Fines Policy Rules provides that in the case of multiple contraventions concerning the same or related processing activities, the total fine must not exceed the legal maximum penalty for the most serious contravention. That maximum would in this case be EUR 20 million, so there was indeed room for a higher penalty.

Robbing Peter to pay Paul

Especially in the case of the Tax and Customs Administration, which formally acts under the Minister of Finance, the fine is of course very much a matter of “robbing Peter to pay Paul”. The question then quickly arises as to whether it actually benefits the data subject. The fines do, however, send a clear signal, one that will not go unnoticed in political circles and that will also have its effect on the future from the legal point of view. When the fine was announced, the chairman of the DPA, Aleid Wolfsen, called for generous compensation for those affected who had been included in the FSV without any well-founded suspicion of fraud. The Dutch government has indicated that it is open to this. That is understandable: After all, in the absence of proper compensation, the issue would seem to be eminently suitable for a class action claim.